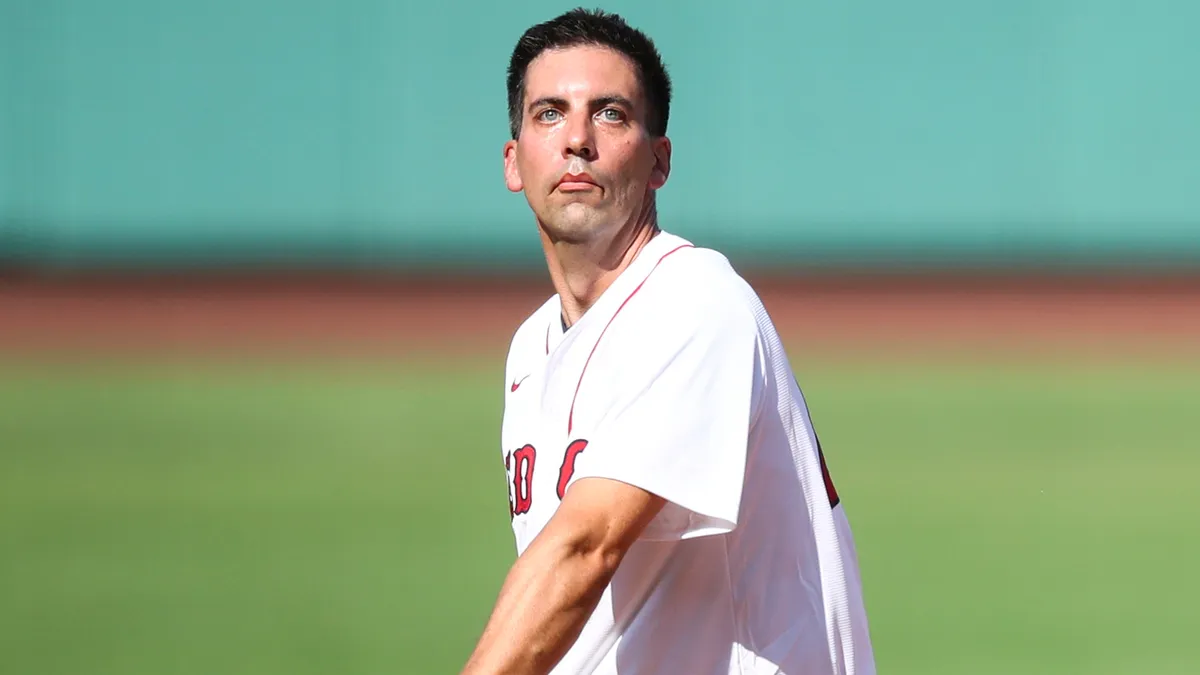

Tim Wakefield was one of us. A member of the Red Sox, he wore the uniform longer than any pitcher in franchise history.

Tim Wakefield was one of us. A knuckleballer, he didn't look like a fearsome athlete and he certainly didn't throw like one. He dazzled the game's greatest hitters with a pitch we all grew up Wiffle-balling into the back of a lawn chair.

But most importantly, Tim Wakefield was one of us. The native Floridian loved Boston, and he made it his mission to serve the city, especially children with cancer. No one worked more tirelessly for the Jimmy Fund and the Red Sox Foundation, and certainly not so selflessly.

Stay in the game with the latest updates on your beloved Boston sports teams! Sign up here for our All Access Daily newsletter.

Whatever you've heard about Wakefield's charitable endeavors, they're nothing compared to the acts that went unpublicized. If there's a Hall of Fame for walking that walk, waive the waiting period and put Tim Wakefield in it tomorrow.

"Devastating" doesn't begin to describe the news that Wakefield died of brain cancer on Sunday at 57.

BOSTON RED SOX

The world beyond his closest friends didn't even know he was sick until former teammate Curt Schilling appallingly shared the diagnosis without permission late last week. Even then, few realized the precariousness of his condition until Sunday's awful announcement. That Wakefield spent his final days navigating the fallout from Schilling's despicable selfishness is almost too much to bear. His family wanted privacy, and at the end, they did not have it. He deserved to die on his own terms.

That's on Schilling. Wakefield, at least, departs with a lasting legacy both on the field and off. Only former teammate Roger Clemens and Hall of Famer Cy Young won more games in a Red Sox uniform, and no one threw more innings.

From his humble beginnings as a 1995 reclamation project who improbably ripped off a 14-1 start, to the 2003 Aaron Boone homer he feared would haunt him, to the redemption of the 2004 World Series just a year later, Wakefield staked a prominent place in Red Sox history over 17 seasons.

He swallowed his ego repeatedly, from being left off multiple postseason rosters, to jerking between the bullpen and rotation, to signing perpetual $4 million options that made him a 200-inning bargain. He prioritized the ability to wear the Red Sox uniform over all else.

Behind the scenes, he could be curmudgeonly but lovable, gruff but kind, a crossword in his lap pretty much anytime you entered the Red Sox clubhouse. I sat next to him on the dais at the Boston Baseball Writer's dinner in the early 2000s and he couldn't have been friendlier. His wife, Stacy, hailed from Brockton and I grew up in nearby Mansfield, so we chatted about that little corner of the world, from Rocky Marciano to Marvin Hagler to former Patriots quarterback Steve Grogan, who bought the local sporting goods store in my hometown from Rocky's brother.

This was a good 20 years ago, and even then, Wakefield liked the idea of settling here when his career was over.

Except, for a while it looked like he might play forever. He won 17 games in 1998 and then saved 15 a year later. He was well on his way to earning the MVP of the 2003 ALCS before fate intervened in extra innings, and I'll never forget his shock in the bowels of Yankee Stadium after that infamous moment as he wondered if he'd be blamed forever, his voice barely above a whisper as he invoked Bill Buckner.

"The Red Sox wouldn't have been here without you," a reporter said, and it wasn't crossing any lines of professionalism, because it was true.

A year later, he helped save the season by volunteering to eat more than three innings of a lopsided loss to the Yankees in Game 3 of the ALCS. That gave manager Terry Francona fresh arms for Game 4, and the Red Sox ultimately became the first team to rally from a 3-0 hole en route to the World Series that ended their 86-year title drought. Wakefield won Game 5 with three innings of shutout relief.

When he made his first and only All-Star team in 2009 just a month before his 43rd birthday, the entire clubhouse cheered him off to St. Louis, where he met President Obama. A year later, he won the Roberto Clemente Award for community service, an honor he could've received about a dozen times.

In September of 2011, the Red Sox poured champagne when Wakefield won the 200th and final game of his career at age 45. He retired the following spring, because if he couldn't play for the Red Sox anymore, he wouldn't play for anyone.

Thus began his second act as a full-time presence for the Jimmy Fund and Red Sox Foundation, which named him its honorary chairman. His Wakefield Warriors program brought sick kids onto the field for batting practice, and Wakefield worked relentlessly behind the scenes at the Franciscan Hospital for Children and Dana-Farber; I guarantee they're sobbing at those institutions and many others today.

Wakefield stayed front of mind by joining the NESN broadcast booth, where friends and coworkers marveled at his ability to remain composed despite a serious cancer diagnosis for his wife in spring training.

Little did anyone know that the disease Wakefield had worked so tirelessly to eradicate would ultimately claim his life, robbing Boston of one of its most devoted citizens.

He had a platform, and he never stopped using it, because he wasn't just one of us, he was the best of us.